Biodiversity

As a nation, Australia is losing biodiversity at an alarming rate.

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water states that Australia supports somewhere between 600,000 and 700,000 species, a large proportion being endemic. Over the past 200 years we have lost more mammal species than any other country – we are world leaders! There are probably numerous species that have recently gone extinct that we don’t even know about because we are very bad at surveying and reporting our native flora, fauna and fungi populations.

|

| Trees provide habitat |

In a report in January this year, the Biodiversity Council listed the main causes of nature loss in Australia as: habitat loss or fragmentation due to land clearing and urbanization, introduction of invasive species, modification of our rivers and wetlands and climate change.

From 2000 to 2017 more than 7·7 million ha of habitat in Australia was cleared, with more than 90% of it NOT being referred to the (ineffective) Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act for approval – Society for Conservation Biology – “This noncompliance means that potential habitat for terrestrial threatened species, terrestrial migratory species, and threatened ecological communities have been lost without assessment, regulation, or enforcement under the Act.”

|

| Credit: Carbon Positive Australia |

Climate Change

Surely

everyone by now is aware of the human effect on global warming – we are pumping

too much carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide is a major

greenhouse gas. Greenhouse gases trap heat in the atmosphere, causing the

planet to heat up.

Trees are natural carbon storage machines. Through photosynthesis, they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and lock up the carbon in their leaves, branches, trunks and roots. “… the restoration of trees ranks among the most effective strategies for climate change mitigation available today.” – Zurich Insurance Group.

“A mature eucalypt woodland can store between 70 and 195 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per hectare” - ‘Farming Carbon’ Qld Govt..

Research conducted for Environmental Science and Policy found “From 1844 to 2010, extreme heat events have killed at least 5332 people in Australia. Since 1900, they have killed more people than the sum of all other natural hazards.”

|

| Credit: The Coversation |

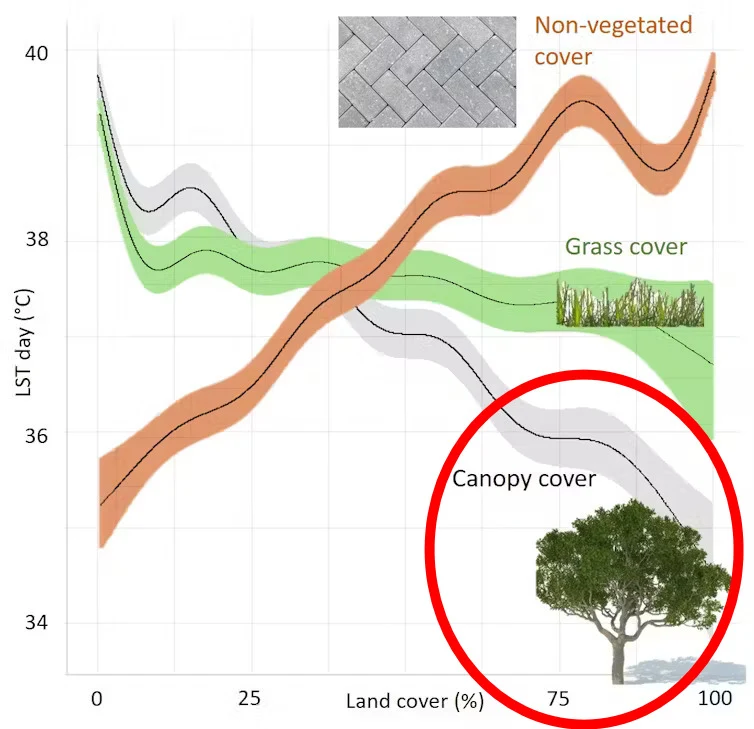

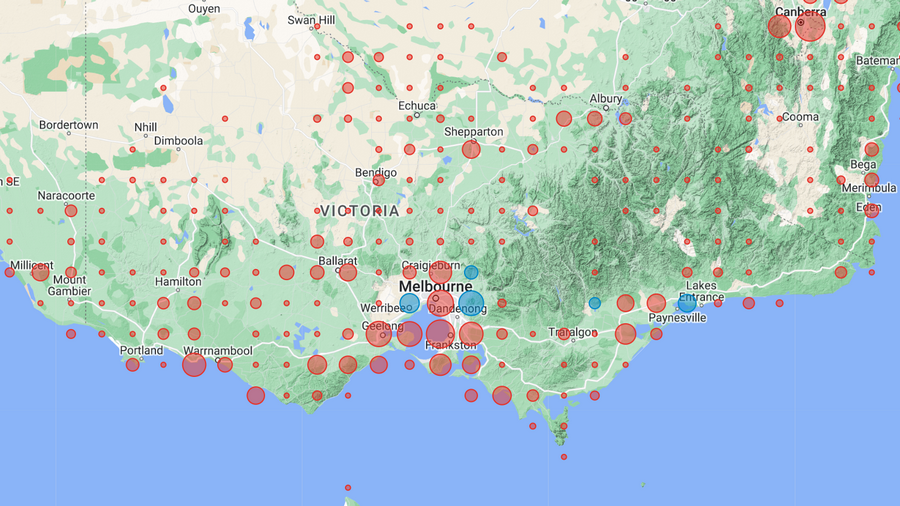

Cities around the world have shown that the urban heat island effect is mitigated by planting trees that provide shade and evapotranspiration.

|

| Urban trees provide shade |

Tree planting is a simple nature-based method of cooling our urban spaces. Why oh why aren’t we doing more?

Post Script: The World Meterological Organisation has just announced that 2024 is likely to be the hottest year on record. The UN Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres, describes it as 'climate breakdown'.

.JPG)

.png)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.JPG)

.JPG)

%201200x1800.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.png)

.png)

.png)